Federal Study Warns Oil Industry Nowhere Near Prepared for Spill in Arctic

A new study from the National Research Council is warning that neither the science nor the currently available public or private response infrastructure is anywhere near prepared for an oil spill in the Arctic Ocean.

The findings, funded by multiple federal agencies as well as the oil and gas industry, offer a potent new obstacle to attempts to drill in the Arctic, particularly as the study’s publication follows a string of related setbacks. Environmentalists say the new research validates warnings they have been voicing for years.

“We’re now seeing much more attention placed on science in the Arctic, as often happens when an area becomes commercially significant. Yet this report is saying that, currently, we don’t know very much at all,” said John Deans, an Arctic campaigner with Greenpeace USA, in an interview with MintPress News.

“In our view, if you don’t know enough about a place—in this case, what either an oil spill or a response would look like—then you really shouldn’t be up there to drill in the first place.”

The new report is the first time in a decade that the National Research Council has looked at the issue, though during that time the situation in the Arctic has changed dramatically. Climate change-related sea ice is melting at a historic rate, opening up a spectrum of nascent commercial opportunities.

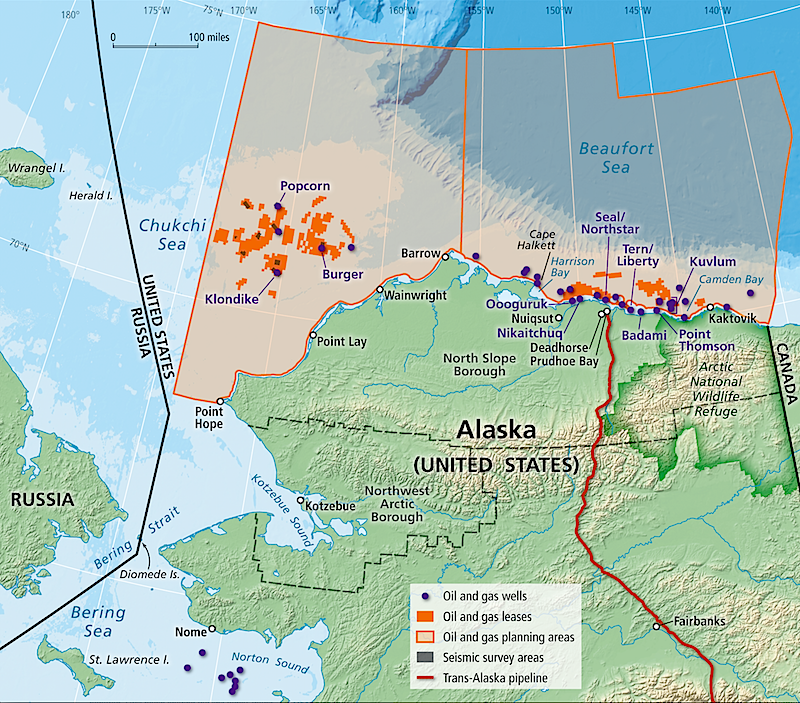

One of the most lucrative of these opportunities would likely be major petroleum reserves. The Arctic region generally is thought to hold some 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas, in addition to 13 percent of undiscovered oil. Thus far, Russia has made the most notable progress in beginning to tap these reserves, with the U.S.-based ExxonMobil having also signed an agreement to drill in the Russian Arctic. Just this week, Russia’s first shipment of offshore Arctic oil was purchased by a French company, Total.

Yet it was only in 2012 that Total’s chief executive, Christophe de Margerie, noted that Arctic drilling posed too big of a risk for both fragile ecosystems and the company’s public image. The new National Research Council findings strongly back those concerns, pointing out significant—in some cases, almost complete—gaps in terms of response capability and scientific understanding of how a major Arctic oil spill would act.

‘Significant Liability’

Technically, U.S. law requires that companies responsible for any oil spill also be responsible for the response. Yet in reality, local, state and federal government bodies are the ones that actually carry out that response. In the Arctic, the report finds, this capability is extremely limited, and building it up would take massive funding.

“The lack of infrastructure and oil spill response equipment in the U.S. Arctic is a significant liability in the event of a large oil spill,” the report warns. “Building U.S. capabilities to support oil spill response will require significant investment in physical infrastructure and human capabilities, from communications and personnel to transportation systems and traffic monitoring.”

Where exactly this funding would come from is unclear. The report suggests a public-private partnership, though this would inevitably be seen as a strengthening of already unpopular public subsidies that benefit the oil and gas industry.

There is also little concrete understanding of how the extreme cold would affect either spilled oil or some of the commonly used remediation techniques in the aftermath of a spill, such as chemical dispersants meant to speed up natural microbial degradation. Indeed, the National Research Council scientists who looked into the issue ultimately went as far as to suggest carrying out a controlled oil spill as the only way to truly answer a host of related questions.

“Laboratory experiments, field research and practical experience gained from responding to past oil spills have built a strong body of knowledge on the properties of spilled oil and response techniques. However, much of this work has been done for temperate regions,” the report notes.

“There is … a need to validate current and emerging oil spill response technologies in Arctic environmental conditions on operational scales. Carefully planned and controlled field releases of oil in the U.S. Arctic would improve the understanding of oil behavior [the Arctic] and allow for the evaluation of new response strategies specific to the region.”

Shell’s Example

Three oil and gas companies have already won approval to explore U.S. Arctic territory: ConocoPhillips, the Norwegian company Statoil and Shell Oil.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe