Even before the Supreme Court’s controversial “Citizens United” ruling, campaign finance laws had blurred the lines between dollars and words.

It never seemed to matter that polls have long shown nearly 80 percent of us disagree with this notion that money is simply an extension of the voice we use to express our views and should therefore be unlimited. For decades, all that has really mattered is that the elected officials who could fix this broken system are the primary beneficiaries of its democratic shortcomings. Hence, money still talks and in Colorado, more loudly than in most places.

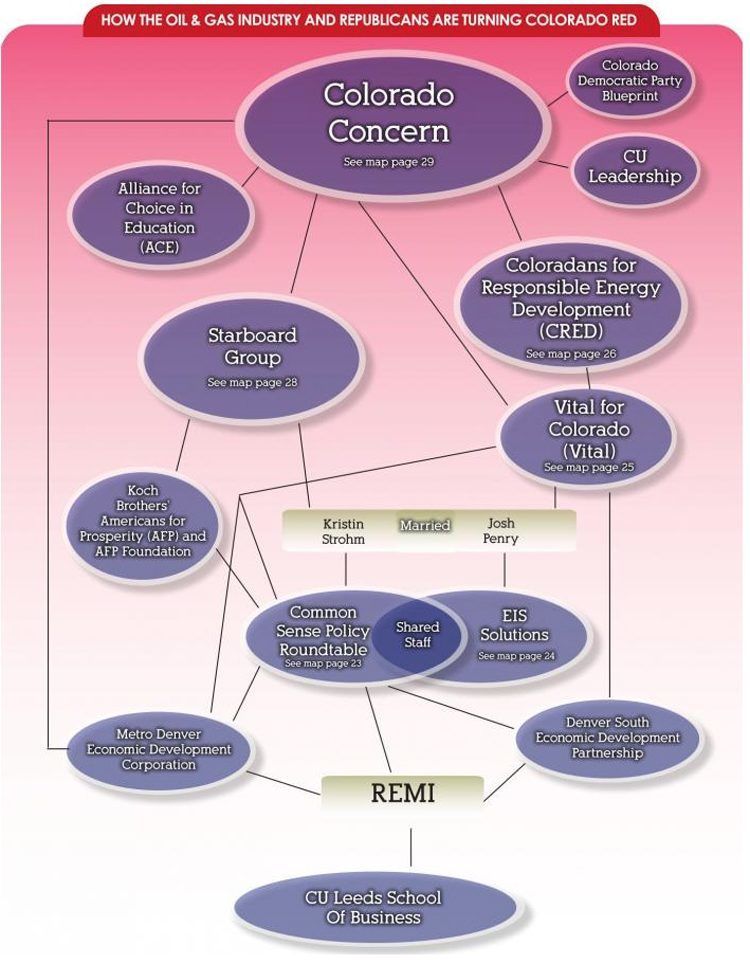

To understand how a handful of wealthy, influential individuals, along with the oil and gas industry and a few key political operatives, have managed to play puppeteer over our state government and even the electorate is quite complicated. That’s why we’ve included seven full pages of what I refer to as “influence maps” at the end of this article.

It has been more than a decade since Democrats came up with their now well-documented “Blueprint,” wherein four billionaires used their massive wealth to flip the state from red to blue. But after the 2014 election cycle, it is abundantly clear that the Republicans—along with a few key “Dems”—now have their own “Redprint,” which, like its blue predecessor, has worked quite well.

Substantially influencing a state’s elections, laws and regulations takes more than just spending $50 million dollars on TV, radio and newspaper ads, although that’s an important part of the equation. It also takes more than just filling the campaign coffers of politicians, although that too has its place.

In order for a microscopic minority of the monied to hold real influence over the rest of us and our democratic system of government, it requires creating the illusion that millions of people and nearly all the research on any given issue supports this minority’s specific point of view. This “illusion building” process is where the political operatives enter the picture.

In Colorado, I like to imagine this political slight of hand as a massive network of loudspeakers mounted on poles in every community across the state. Every few minutes the same message blares out over the speakers: “oil and gas and fracking are good for you because jobs, economy, freedom, American flag, natural gas is the new green, Middle East terrorists … blah, blah, blah.” The only thing that changes, in my imagined scenario, is who’s delivering the message, as nearly every blast appears to come from a brand new grassroots organization. Most of us assume these grassroots groups are made up of thousands of folks just like us. And besides, they have really intriguing names like “Citizens for the Environment Who Like Shale Oil,” or the “Clean Air Coalition for Freedom From Terrorists,” or “Mothers for Tar Sands.” You get the point.

Next, I imagine that all the wires coming from all the poles holding the loudspeakers form a giant interconnected web that covers the state like lace, but ultimately, all those wires lead back to just one small room in an office building in Denver. Inside that room, a handful of political operatives take turns at the mic pretending to be a member of the next new group who just has to tell you how much shale oil means to them while throwing in a bunch of facts and figures from seemingly credible sources, which, in the hands of these professional twisters of the truth, scare us into thinking the sky will fall, the economy will collapse and most children will go hungry if oil companies can’t stick rigs in the middle of our neighborhoods.

And that’s where this investigation comes in, because that room, or some wall-less facsimile thereof, does exist. So who is in that room, where do they get their facts and, more importantly, who pays for the whole operation are very real, very important questions.

About Those Facts

Editors Note: A few months back, Boulder Weekly agreed to pay for half the cost of a Colorado Open Records Act (CORA) request concerning certain emails at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Leeds School of Business. We split the cost with Greenpeace, who submitted the CORA and then provided us our copy of the emails. In the end we were given more than 2,000 pages, some heavily redacted, most not. This investigation and the information in this article came entirely from Boulder Weekly’s own work. We had been tracking the creation of the oil and gas industry’s network of front groups and the Republican Party’s funding apparatus since the fall of 2014. These CORA documents helped us to further understand the complex interconnections of both.

I remember the first time I heard someone say they thought something fishy might be going on at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Leeds School of Business. It was in October 2013, as we were pulling together our annual vote guide and endorsements package. I don’t remember who said it, but someone uttered something like, “Leeds must be on the payroll of ‘Vote NO on 66’.”

It wasn’t a serious accusation. It was simply a way of noting that Leeds’ research on the issue seemed out of step, and quite popular with the “vote NO” crowd.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe