The Inside Story of How a University Professor Quietly Collaborated With Monsanto

Former University of Illinois food science professor Bruce Chassy is known for his academic gravitas. Now retired nearly four years, Chassy still writes and speaks often about food safety issues, identifying himself with the full weight of the decades of experience earned at the public university and as a researcher at the National Institutes of Health. Chassy tells audiences that before he retired in 2012, he worked “full time” doing research and teaching.

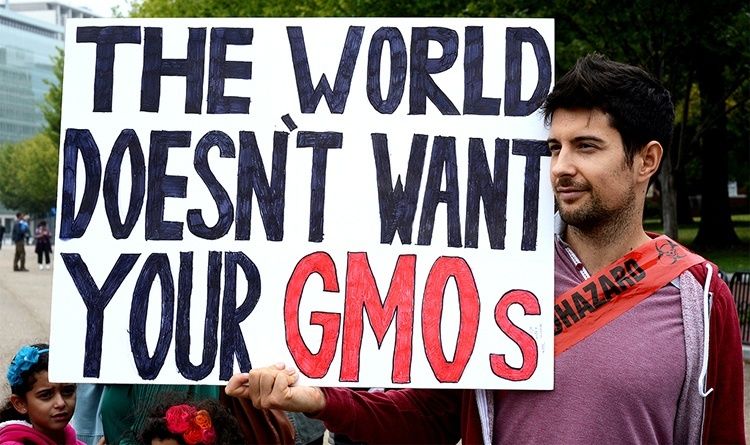

What Chassy doesn’t talk much about is the other work he did while at the University of Illinois—promoting the interests of Monsanto Co., which has been trying to overcome mounting public concerns about the genetically engineered (GMO) crops and chemicals the company sells. He also doesn’t talk much about the hundreds of thousands of dollars Monsanto donated to the university as Chassy was helping promote GMOs or Monsanto’s secretive role in helping Chassy set up a nonprofit group and website to criticize individuals and organizations who raise questions about GMOs.

But emails released through Freedom of Information Act requests show that Chassy was an active member of a group of U.S. academics who have been quietly collaborating with Monsanto on strategies aimed at not just promoting biotech crop products, but also rolling back regulation of these products and fending off industry critics. The emails show money flowing into the university from Monsanto as Chassy collaborated on multiple projects with Monsanto to counter public concerns about genetically modified crops (GMOs)—all while representing himself as an independent academic for a public institution.

A New York Times article by Eric Lipton published last September laid bare the campaign crafted by Monsanto and other industry players to use the credibility of prominent academics to push the industry’s political agenda. That New York Times article focused primarily on University of Florida academic Kevin Folta, chairman of the university’s Horticultural Sciences Department and Folta’s work on behalf of Monsanto. But an examination of recently released email exchanges between Monsanto and Chassy show new depths to the industry efforts.

The collaborations come at a critical juncture in the U.S. regarding GMO public policy. Mandatory GMO labeling is set to take effect in Vermont on July 1; Congress is wrestling over a federal labeling law for GMOs; and several other states are seeking their own answers to rising consumer demand for transparency about this topic.

Many consumer and environmental groups want to see more restrictions and regulation on GMO crops and the glyphosate herbicide many know as Roundup, which is used on GMOs. But the companies that market the crops and chemicals argue their products are safe and there should be less regulation, not more. Monsanto’s roughly $15 billion in annual revenue comes almost exclusively from GMO crop technology and related chemicals.

Amid the furor, the revelations about corporate collaboration with public university scientists to promote GMOs have sparked a new debate about a lack of transparency in the relationships between academics and industry.

Chassy has said he did nothing unethical or improper in his work supporting Monsanto and the biotech crop industry. “As a public-sector research scientist, it was expected … that I collaborate with and solicit the engagement of those working in my field of expertise,” Chassy said.

Still, what you find when reading through the email chains is an arrangement that allowed industry players to cloak pro-GMO messaging within a veil of independent expertise and little, if any, public disclosure of the behind-the-scenes connections.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe