By The Goldman Environmental Prize

The Goldman Environmental Prize honors grassroots environmental heroes from the world’s six inhabited continental regions: Africa, Asia, Europe, Islands & Island Nations, North America, and South and Central America. The prize recognizes individuals for sustained and significant efforts to protect and enhance the natural environment, often at great personal risk. The Goldman Prize views “grassroots” leaders as those involved in local efforts, where positive change is created through community or citizen participation in the issues that affect them. Through recognizing these individual leaders, the prize seeks to inspire other ordinary people to take extraordinary actions to protect the natural world.

Here are the 2016 Goldman Environmental Prize winners:

Baltimore Youth Changes Hearts and Minds to Prevent Toxic Incinerator in Community Beset by Pollution

Last year Freddie Gray’s death put Baltimore at center stage in the national dialogue about race in America. Much of the focus has been on police brutality and differential treatment of racial minorities by law enforcement and the criminal justice system. There has been less attention to the environmental consequences of institutional racism, which are disproportionately experienced by poor people of color.

For decades, residents of South Baltimore have been plagued by pollution from heavy industry. The area hosts the nation’s largest medical waste incinerator, alongside chemical plants, coal piers and associated diesel-truck traffic. The small neighborhood of Curtis Bay is the epicenter of a community’s fight against South Baltimore’s aggressive industrial expansion. In recent years, it was determined to have the worst toxic air pollution in the U.S., but development continues apace.

The latest threat is another behemoth—the nation’s largest trash incinerator. The project’s legal approval was secured by developer Energy Answers under the pretense that the facility would produce renewable energy as clean as solar and wind by burning waste. The reality is different. Although Energy Answers’ incinerator was ranked in “tier 1” of Maryland’s Renewable Portfolio Standard, research revealed that it would wreak havoc on the community’s health and environment. It would emit vast quantities of toxic heavy metals such as mercury and arsenic that have been linked to lung cancer, asthma and heart disease—in a community already plagued by industrial pollution.

The only thing standing in the way of the incinerator’s construction is Curtis Bay native and college student Destiny Watford. From the age of 16, she mobilized her disaffected community to fight the incinerator using social media and performing arts, coupled with a creative strategy to limit Energy Answers’ ability to fund the project.

Watford, now 20, became an environmental activist when she learned about Energy Answers’ proposal to build the incinerator in Curtis Bay. Her first-hand experience watching neighboring towns wither from industrial pollution motivated her to protect her battered community. With clear-eyed enthusiasm, Watford and other public high school students united the people of Curtis Bay in support of their efforts.

After attempts to halt the project by invoking local health-related regulations were unsuccessful, Watford turned to arts and information as modes of activism. Inspired by a play she saw about pollution and deception, Watford called for her schoolmates to utilize their passions in videography and design to put pressure on 22 local organizations—including the Baltimore City Public School system—that had pledged to purchase energy generated by the as-yet-unbuilt incinerator. Through education she provided about the incinerator’s impacts, Watford convinced 18 of the 22 organizations to nullify their contracts, effectively cutting off the main source of revenue for the incinerator.

However, the threat of the incinerator looms. Energy Answers still holds the lease on the 97-acre site, and Watford has reached an impasse with the Maryland Department of Energy, which has the ability to force Energy Answers out since it violated its permit by not beginning construction.

Despite this, Watford is not sitting idle. She has a vision to transform the site for the true benefit of the community by exploring alternatives like solar technology, filling the site with community-owned panels to make it the largest solar farm on the eastern shore board. This would provide clean energy jobs for locals and would be a first step to encourage sustainable development. Toward this end, Watford is collecting signatures and video testimonials appealing to the Maryland Department of Energy to enforce the law and evict Energy Answers. With enough support, Watford hopes to begin the process of re-claiming Curtis Bay for its resident.

Watch here:

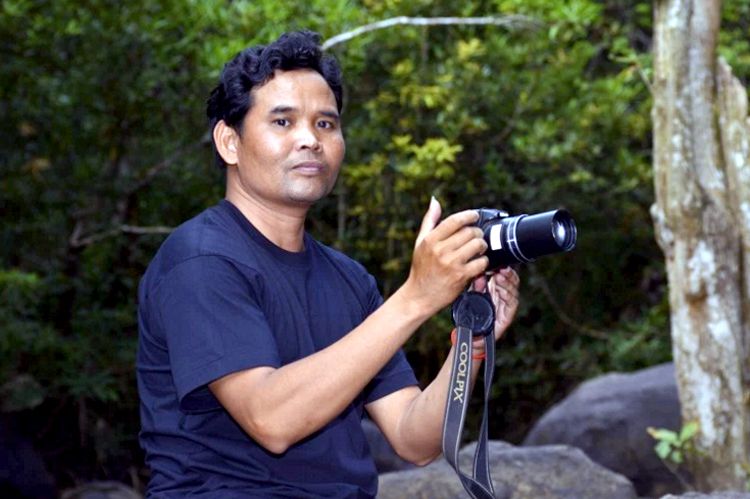

Uncovering Phnom Penh: Cambodian man reveals government’s destruction of indigenous farmers’ homes and forest land for timber sales

In Cambodia, where eighty percent of the population depends on the land for its livelihood, large swaths of forest and arable land are being taken from farmers and destroyed. The seizures are permitted by a 2001 law that allows the government to take over citizens’ property for development purposes through deeds called Economic Land Concessions (ELCs). Under the guise of clearing space for agricultural and industrial projects, the government has used ELCs to force 300,000 rural Cambodians off their land. Once the people are removed, timber companies illegally fell rare trees such as the Siamese Rosewood to make luxury wood furniture for the international market, mostly in China and the U.S. While a handful of companies with powerful political allies have made a fortune on the illicit sale of exotic timber, Cambodian villagers have been left homeless, jobless and hungry.

Ouch Leng, 39, grew up in the post-Khmer Rouge era when government corruption, violence and impunity for elites were ubiquitous. Ouch vowed from an early age to dedicate his life to protecting Cambodia’s forests and defending the human rights of his people. As land grabbing via ELC deeds accelerated, Ouch founded the Cambodian Human Rights Taskforce (CHRTF), a nonprofit organization focused on exposing human rights violations behind ELCs. His work bridges human rights and environmental defense because ELC-initiated deforestation ravages wildlife habitat and devastates indigenous populations. Through his investigations into ELC-related human rights violations, Ouch found that most illicit logging occurred under deeds issued to Try Pheap, a Cambodian logging tycoon with close ties to Prime Minister Hun Sen.

For years, Ouch worked undercover, posing as a Try Pheap Group employee or hiding in muddy fields near logging sites to gather firsthand evidence of Try Pheap’s criminal activity and of his company’s alliance with the Cambodian government. Following multiple clandestine research initiatives, Ouch released findings to the international media, which demonstrated that Try Pheap and high-ranking government officials were colluding in illegal timber trade. Since then, Ouch and CHRTF have released a series of reports detailing the malfeasance. When the government was undeterred by the embarrassing revelations, Ouch mobilized Cambodian citizens to stage peaceful protests in the streets of Phnom Penh and block the illegal loggers from accessing their land. The added pressure from the protests led the government to nickname Ouch the “Land Revolution,” as his activism was beginning to threaten the ELC system and the government’s timber fortune.

In 2014, much as a result of Ouch’s persistence, the government cancelled nearly 50,000 acres of ELCs granted to Try Pheap Group inside the Virachey National Park, which is home to sun bears, small-clawed otters and dholes, an endangered species of wild dog.

Ouch’s work has put him at immense personal risk. It is unusual for a whistleblower in Cambodia to be so openly critical and willing to identify himself. A Global Witness report released last year revealed that Cambodian activists have been killed for standing up against these injustices. Today, Ouch lives in hiding following numerous threats to him and his family. Despite this danger, he continues fighting rampant government corruption to save the Cambodian forest for future generations.

Ouch wants to make the international community aware of the devastation caused by ELCs and illegal logging. To discourage the government from continuing this practice, Ouch calls for people around the world to make sure any wood furniture they purchase is sourced sustainably.

Watch here:

Puerto Rican Man Saves One of the Island’s Last Few Pristine, Undeveloped Coastal Strips

For more than 15 years a battle has been fought over a segment of pristine coastline on the Atlantic tip of Puerto Rico known as the Northeast Ecological Corridor (the corridor). The 3,000-acre area nestled between the seaside municipalities of Luquillo and Fajardo is highly biologically diverse. Comprised of a patchwork of public and private parcels, the corridor is home to nearly 900 varieties of flora and fauna, including several endangered species such as the leatherback sea turtle. Often referred to as an “ecological wonderland,” the corridor packs coastal wetlands, mangroves, tropical rain forest and desert-like habitat into a relatively small area.

In the 1990s, private developers seeking prime real estate for luxury hotel projects quietly arranged with politicians to build two mega-resorts along corridor beaches. Residents and environmental advocates didn’t want the untouched area to succumb to development like so many other places in Puerto Rico. One local man has steadfastly combined legal savvy and traditional organizing to unite communities against the development.

Luis Jorge Rivera Herrera, 43, is an environmental scientist who grew up on a family farm near Luquillo that has been passed down through four generations. Living and surfing in the corridor, Rivera Herrera was awestruck by nature from an early age. Rivera Herrera was especially taken by the massive female leatherback sea turtles that haul themselves onto the beaches to lay eggs. Then hatchlings, scarcely the size of a human hand, scamper into the ocean. The corridor is one of a dwindling number of suitable nesting sites for the largest species of sea turtle. Rivera Herrera believes the corridor is Puerto Rico’s natural patrimony, and that it should be kept safe for humans, sea turtles and other wildlife to enjoy.

When the Puerto Rican government announced proposals to build the San Miguel and Dos Mares resorts in 1999—projects that were backed by Marriott and Four Seasons—Rivera Herrera sprung into action. He gathered data about the corridor’s ecosystems and paired it with details about the resorts’ construction plans. Rivera Herrera brought this information to the communities, and he also brought community members to the proposed resort sites to emphasize what was at stake.

After years of raising awareness among local people, Rivera Herrera founded the Coalition for the Northeast Ecological Corridor (NECC) in 2005 to formalize his volunteer efforts and those of community groups. This included the Puerto Rico chapter of the Sierra Club, which had recently been established on the island with the corridor’s conservation as its flagship issue. This marked a turning point for the campaign.

Rivera Herrera initiated a legislative act to protect the corridor as a nature reserve. The bill failed to pass in the legislature, but Governor Aníbal Vilá saw enough public support to pass an executive order in 2007. However, in a stunning example of the precariousness of legal protections, the next governor, Luis Fortuño, repealed the corridor’s designation a mere two years later. This repeal caused speculation about the independence of Fortuño’s decision given that Dos Mares resort contributed funds to his campaign.

In spite of this crushing setback, Rivera Herrera parlayed widespread public outcry over Fortuño’s reversal to mount a second attempt to pass a bill that would permanently protect the corridor. His legislative campaign found success in 2012, and the following year, Governor Alejandro García Padilla signed the bill into law, protecting the corridor’s public lands and ending the threat of development.

Due to financial constraints that have prohibited Puerto Rico’s Department of Natural and Environmental Resources from hiring a manager for the newly protected corridor, Rivera Herrera is acting as interim manager. He is working with others to develop a plan to develop sustainable tourism in the corridor. His biggest challenge, however, is raising funds to purchase the private parcels that remain in the corridor, a condition of the bill that must be met within eight years. The government earmarked funds for this purpose but they are in jeopardy due to Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis.

Watch here:

Environmental Lawyer Breathes Life into the Law to Stop Landfills in Slovakian Villages

For years, Slovakia has been a cheap and willing customer in the dumping of Western EU countries’ waste. Its loose construction laws—which govern the management of waste disposal facilities—do little to prevent under-the-table deals between the national government and private developers, while individual municipalities are left with little choice but to store unwanted waste that they have no hand in approving. As a result, in villages across Slovakia illegal landfills sit just meters away from residential areas and leach toxic chemicals into the soil and groundwater. They also release pollutants into the atmosphere, creating environmental and human health hazards that last for decades.

At a glance, the town of Pezinok—located just 13 miles outside the capital of Bratislava—seems to be an exception. Vineyards that once produced royal wine surround the small town at the base of the Little Carpathian Mountains. Yet, the rate of leukemia in Pezinok is eight times higher than the Slovak average. A landfill built in the 1960s, without any permits, sits at the town’s edge, containing waste from medical facilities and chemical factories. Despite Pezinok’s 2002 urban plan, which prohibited landfills within the city limits, construction began on a second landfill in 2003 due to the owner’s connections with regional authorities. Though the country’s nascent democratic system that operates on clientelism would have ordinarily provided an easy path for this new project, one community member began a fight that would challenge ‘business as usual.’

Zuzana Caputova, 42, resides in Pezinok with her two young children. Having been born and raised in the town, the environmental lawyer was all too familiar with the negative effects of its illegal landfill. When the local people needed a leader to fight against the new landfill, they reached out to Caputova for help. But Caputova did more than mobilize her community. She combined legal know-how and bottom-up activism to take on the Slovakian people’s illegal dumping problem in law and in practice.

Noted as one of the largest grassroots efforts since the Velvet Revolution, Caputova’s fight to stop Pezinok’s landfills marked one of the first times local residents took a stand on the waste dump issue. Caputova filed injunctions to shut down the older landfill, then turned her attention to halting construction on the new landfill before it was too late.

While Caputova and her public advocacy law firm, Via Iuris, filed petitions with officials to stop the new landfill, she also encouraged residents to organize. What resulted was a citizens’ initiative called “Dumps Don’t Belong in Towns,” as well as the uncovering of illegal permits that gave Caputova the indisputable evidence she needed. By empowering others, Caputova inspired a demonstration involving 67,000 locals that convinced the municipality to acquiesce and cease the landfill construction.

But Caputova’s fight did not end in Pezinok. In 2014, residents of nearby village, Smolenice, contacted her. They had heard of Pezinok’s success and sought Caputova’s help to stop a waste gasification plant that would convert garbage into fuel and electricity using a new, untested technology. The people of Smolenice didn’t want to be guinea pigs. Caputova helped them prevail and since then eight other municipalities in Slovakia facing similar struggles have received help from Caputova.

Notably, Caputova has set her sights at the federal level to address the legal root of the landfill issue once and for all. She recently assisted in drafting an amendment to Slovakia’s 49-year-old Construction Law—the source of the problem when it comes to the harmful effects of waste storage. The amendment would give a larger voice to municipal governments and increase public participation in the waste disposal and landfill development process. The Construction Law will be reviewed by parliament in March of 2016 and many have indicated support for the amendment.

To further the legal assistance of many Slovakian municipalities—and strengthen the country’s judiciary system through advocacy—Caputova is encouraging all supporters to donate to Via Iuris, the not-for-profit public advocacy firm that she has partnered with to fight these landfills and challenge the Construction Law.

Watch here:

Peruvian Grandmother’s Struggle to Stop Mega-Mine in Andean Highlands

Like many developing countries, Peru is the site of natural resource extraction projects that drive out local people with legal rights to their land. Corrupt private partnerships with regional governments and international investors leave the ordinary people whose lives are affected with nowhere to turn. But in a remote corner of Peru’s northern highlands, one woman has put a wrench in the plans of Colorado-based Newmont Mining Corporation, which is angling to build a huge mining project in her backyard.

Máxima Acuña, 47, is a subsistence farmer, grandmother and unwitting activist whose fight to prevent Newmont from building the Conga Mine was born of her drive to protect her land and her right to peacefully live off of it. An unconventional environmental champion, Acuña has no formal schooling nor is she affiliated with any advocacy organization. Yet her iron spine and deep sense of injustice have put her at the forefront of a movement to stop the Conga Mine.

More than 20 years ago, Acuña and her husband purchased the land that they live on and farm. Their 60-acre homestead is located at the edge of Laguna Azul (Blue Lake), one of several high-altitude lakes that supply fresh water for her family and that of countless others downstream. The stark Andean mountain terrain has rich soil in which Acuña grows her crops, and native grasses that sustain her livestock.

In 2011, the Peruvian government granted Newmont a 7,400-acre concession to build the Conga Mine that included Acuña’s property. In order to move forward with the project, Newmont would need access to Acuña’s land. Her parcel provides optimal access to Laguna Azul, one of four lakes that Newmont plans to drain and convert into tailings ponds to collect toxic mining byproducts such as cyanide and arsenic.

After receiving the concession, Newmont representatives tried to persuade Acuña to sell her property. She refused, knowing that the mine would poison the region’s fresh water, and because she feels a deep connection to the land she has tended for more than two decades. A year later, in 2012, Newmont won a lawsuit against Acuña in a local court, having accused her family of squatting on land Newmont claims it purchased as part of a bundle of properties.

Acuña enlisted the help of GRUFIDES, a local NGO that provides legal assistance for rural communities against mining companies. With GRUFIDES’ help, Acuña appealed the local verdict in a higher regional court, often walking 10 hours over treacherous mountain paths to make her court appearances. In 2014, the higher court overturned the original verdict, lifting the criminal charges against Acuña. While this victory meant that Newmont couldn’t proceed with building the mine, it has come at a high personal cost for Acuña as the company continues to dispute Acuña’s land rights and harass her family.

Since refusing to be bought out, Acuña and her family have been monitored and threatened. Peruvian state police, working as private security contractors on behalf of Newmont and its subsidiaries, tried to evict her and they forbade her from planting crops on her land. Newmont put up a fence around her land, restricting Acuña’s movement. Agents have destroyed her home two times, razing the structure and absconding with her possessions. When Acuña and her daughter tried to intervene they were beaten unconscious.

Despite relentless harassment, Acuña is standing her ground. She never sold her land to Newmont and won’t hand it over. In the oral tradition, Acuña sings about her struggle to protect the land and her way of life. The lyrics of her songs communicate her wisdom and her voice reflects the trauma she has endured. However, Acuña’s open expression and warm smile convey that she won’t allow her spirit to be crushed.

Newmont may appeal the regional court’s decision in the Peruvian Supreme Court in order to move forward with the mine. For the time being, Acuña has managed to block the construction of the Conga Mine in a region of Peru where one-half of all land has been granted to extraction projects.

Watch here:

Tanzanian Community Leader Secures Indigenous Land Rights through Innovative Use of Land Law

The native people of Tanzania are better known for their colorful cultural expressions than for their innovative approaches to addressing land rights disputes. Despite enduring decades of displacements, pastoralist and hunter-gatherer indigenous communities like the Maasai and the Hadzabe have co-existed with wildebeests, gazelles, rhinoceroses and other mega-fauna in Tanzania’s arid rangelands for more than 40,000 years. Due to government policies that have prioritized foreign investment and development over traditional land use practices, the Maasai and Hadzabe constantly face the threat of losing their land, and with it their ways of life. One man has been able to secure hundreds of thousands of acres of indigenous territory via the creative application of a law intended to manage village land.

Edward Loure, 44, is a member of the Maasai people and is the Program Coordinator for the Simanjiro region with nonprofit Ujamaa Community Resource Team (UCRT). Having grown up during a time when the government forcibly evicted the Maasai from their communities in order to create national parks, Loure was inspired to demonstrate that native peoples are good stewards of the land, caring for ecosystems while practicing traditional livelihood activities such as livestock grazing. Recognizing that the lack of legal documentation demarcating indigenous territory allowed outside actors to buy up land they considered to be unclaimed, Loure set about making the Maasai and Hadzabe’s plans for their ancestral lands intelligible to the state.

During the last 50 years, land that was historically populated by endemic peoples has been sold to commercial hunting and eco-tourism operations, or to large-scale commercial farmers who produce crops for export. To date, the Maasai have lost more than 150,000 acres of rangeland across northern Tanzania. As the supply of available land in Tanzania decreases, pressure on areas managed by the Maasai and Hadzabe, often perceived as ’empty,’ increases. This has resulted in multiple clashes between indigenous people and outsiders. The Maasai and Hadzabe defend against encroachments on their land and reject assumptions that they don’t protect habitat and wildlife.

In 2003, Loure and UCRT set out to address the problem. They began meeting with indigenous community members and village leaders to discuss an unprecedented approach to documenting land rights. Loure used a provision called the Certificate of Customary Right of Occupancy (CCRO) from the Tanzanian Village Land Act to formalize land rights for the Maasai and Hadzabe. The rule was meant to manage individual land holdings within villages; however, Loure used it to recognize land rights on behalf of a community.

When they approached communities about creating CCROs, Loure and UCRT were met with apprehension. Maasai and Hadzabe people had been misled in the past. But over many conversations, Loure worked with communities to map the boundaries of their territories and create land use plans. In the years Loure spent shepherding the creation of CCROs, and navigating conflicts, he gained the trust of the people and earned a reputation for fairness and inclusion. It is not common for a Maasai man to work on behalf of the Hadzabe people but they knew he had their best interests at heart.

By 2013, after nearly a decade of work, Loure had secured more than 200,000 acres of land for the Maasai and Hadzabe using CCROs. For the Hadzabe, Loure negotiated an agreement between the group and Carbon Tanzania, a nonprofit, for the Hadzabe to be paid for the carbon sequestered in their forests.

Loure’s success has inspired other indigenous groups to use the same tactic to protect land, and Loure is currently working on 12 additional CCROs to secure rights for more than 970,000 acres of land, mostly in northern Tanzania.

Looking ahead, Loure hopes the success of CCROs will draw awareness to the issue of land rights for indigenous people and increase support in Tanzania. To further the development of CCROs, Loure and UCRT need funds to support their work. Those interested in helping are encouraged to donate to the local fund for UCRT, here.

Watch here:

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Prize-Winning Activist Berta Cáceres Murdered in Honduras

40 Students Arrested Demanding Their Schools Divest From Fossil Fuels

March 2016 Was Hottest on Record by Greatest Margin Yet Seen for Any Month

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe