The Dead Sea is Shrinking at Alarming Rate, a Record Low-Point for Earth

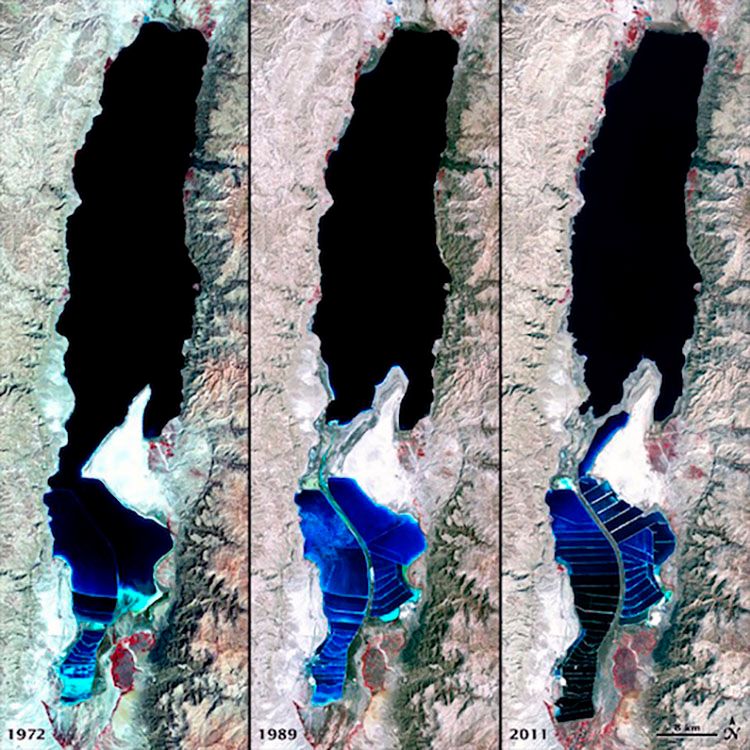

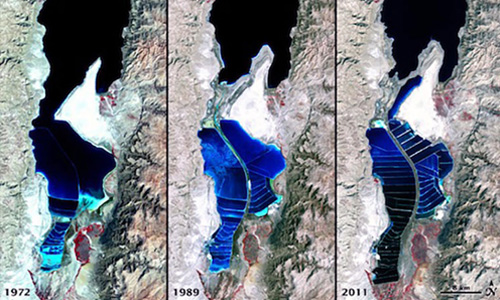

No the Dead Sea is not dying; it’s drying. Well, more like shrinking, by 3 feet each year.

The Dead Sea—the lowest point on Earth at roughly 1,300 feet below sea level—is known for its high salt and mineral content and allowing swimmers to float effortlessly on the surface. The amount of space available for easy floating is shrinking.

The good news is it will probably never dry up completely, the BBC said. As the water level drops, the sea’s density and saltiness rise. Eventually the rate of evaporation will reach a kind of equilibrium and it will stop shrinking.

Just because the Dead Sea is not going to disappear entirely, though, doesn’t mean its shrinking isn’t a concern.

During World War I, according to the BBC, British engineers scratched initials on a rock to mark the sea’s level of water. Now, those marks are on a bone-dry towering rock. BBC’s Kevin Connolly explains where the water level is now compared to back then:

To reach the current water level you must climb down the rocks, cross a busy main road, make your way through a thicket of marshy plants and trek across a yawning mud flat. It’s about 2km (1.25 miles) in all.

Local resorts are feeling the effects, too. At the tourist resort of Ein Gedi, when the main building was constructed, the water from the sea would lap against the walls. Now, the BBC said, the resort has to use a special train pulled by a tractor to take tourists to the water’s edge, roughly a 1.25-mile journey.

“The sea was right here when I was 18 years old, so it’s not like we’re talking about 500 or a 1,000 years ago,” Nir Vanger, who runs the business side of Ein Gedi’s tourist operations, said. “The Dead Sea was here and now it’s 2km away, and with the tractor and the gasoline and the staff it costs us $500,000 a year to chase the sea.”

The farmers are affected, as well. But instead of retreating water lines, sinkholes are their foe. Sinkholes form when underground salt deposits are left behind by the shrinking Dead Sea. The land either collapses or dissolves when fresh water seeps under those spots, the BBC reported. But farmers, who grow tomatoes, bananas and watermelons, refuse to leave the land.

“We’ll never leave,” Salim al-Huwemel, a farmer on the Jordan side of the Dead Sea, said. “Even if the Dead Sea were to rise up and sweep us into a sinkhole. We will always be here.”

Some sinkholes can be 100 meters (328 feet) across and 50 meters (164 feet) deep. Their numbers now top 5,500 around the Dead Sea’s shoreline. Forty years ago, the BBC reported, there were none.

Each year, the number of sinkholes is increasing, and not in a predictable way.

“The number’s not linear,” Gidi Baer, Geological Survey of Israel, told the BBC. “It’s growing and accelerating. This year, for example, about 700 sinkholes formed, but in previous years the number was lower. In the 1990s it was a few dozen, now it’s hundreds.”

The decision to take action and what type of action has been a scientific and political debate for a long time.

Activists want to see something happen.

“We are not talking about saving the Dead Sea because it’s nice or not nice,” Salem Abdel Rahman, a Jordanian activist for the Ecopeace Middle East environmental group, told the BBC. “We think that the Dead Sea is a symptom of sickness in the management of water resources. The saving of the Dead Sea will be a good indication that we moved away from sickness to a healthy environment.”

For now, though, the Dead Sea will just keep shrinking.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

NOAA: World’s Worst Coral Bleaching Event to Continue ‘With No Signs of Stopping’

Methane Emissions From Onshore Oil and Gas Equivalent to 14 Coal Plants Powered for One Year

185 Environmental Activists Across 16 Countries Were Killed in 2015

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe