A plume of exhaust extends from the Mitchell Power Station, a coal-fired power plant built along the Monongahela River, 20 miles southwest of Pittsburgh, on Sept. 24, 2013 in New Eagle, Pennsylvania. The plant, owned by FirstEnergy, was retired the following month. Jeff Swensen / Getty Images

By David Drake and Jeffrey York

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The Big Idea

People often point to plunging natural gas prices as the reason U.S. coal-fired power plants have been shutting down at a faster pace in recent years. However, new research shows two other forces had a much larger effect: federal regulation and a well-funded activist campaign that launched in 2011 with the goal of ending coal power.

We studied the retirement of U.S. coal-fired units from January 2008 to September 2016 and compared the effects of various market factors, regulations and activism on their early closure. In all, 348 coal-fired units either retired or switched to natural gas during that time.

Among the many pressures on coal power that we reviewed, a federal regulation implemented in 2015 had the biggest overall effect. The Cross State Air Pollution Rule requires states to reduce soot and smog pollution that blows across state lines, including from power plants. We estimate that it was responsible for reducing the expected production life of the coal power units that it affected by a total of 1,170 years.

Looking at coal units individually, however, we found that the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, backed by over 4 million to date from Bloomberg Philanthropies, had the most impact per targeted plant.

The campaign works by generating public pressure on utilities and state and local politicians to close down coal-fired units, often through targeted lawsuits. When the Beyond Coal campaign targeted a coal-fired unit, we found that the unit’s life expectancy, normally 50-60 years, was reduced by an average of just over two years.

The Cross State Air Pollution Rule was the second-biggest factor per individual plant, though it affected more plants. It reduced the expected life span of each coal-fired generating unit that it affected by an estimated average of about 21 months.

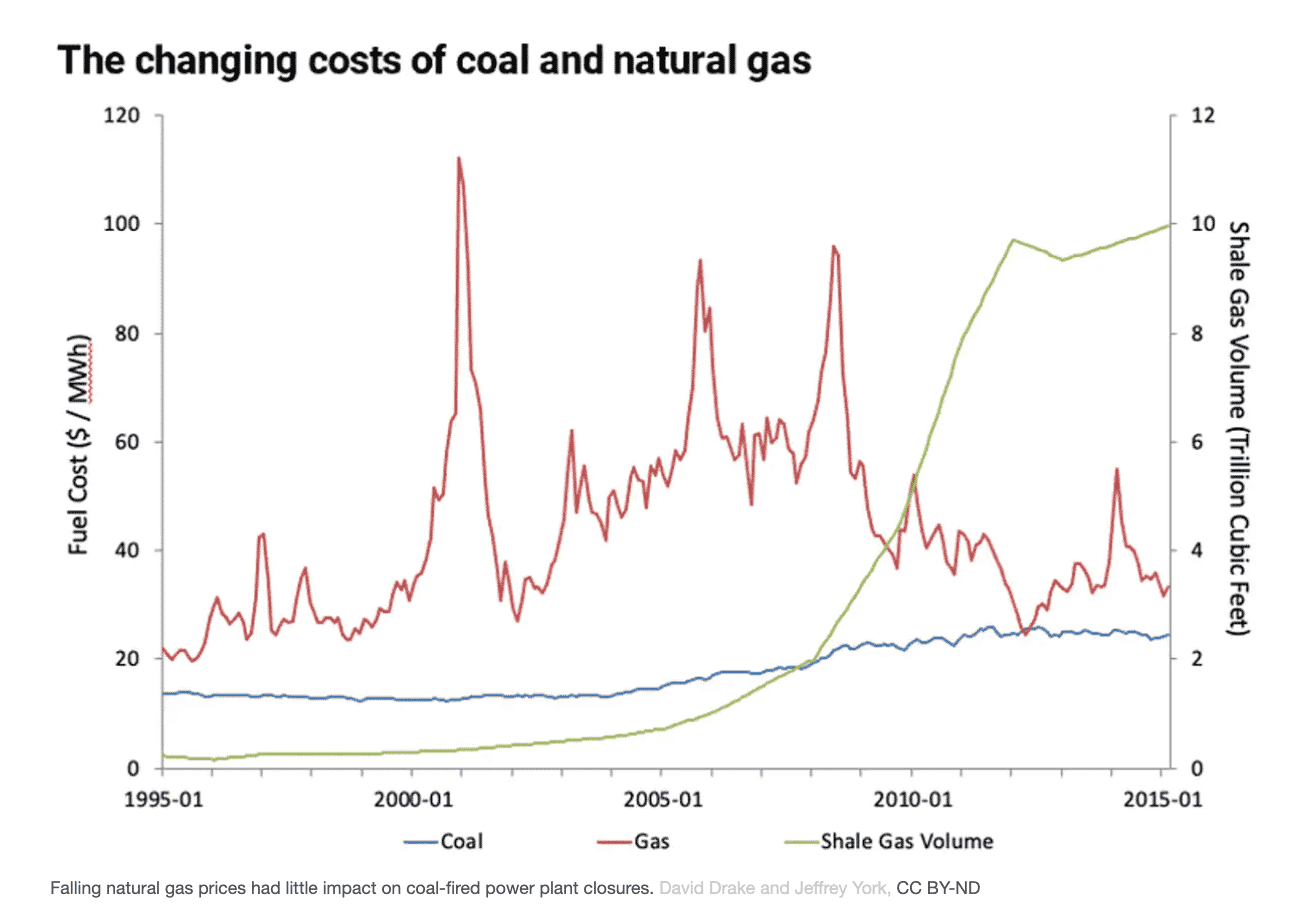

We were surprised to find that neither low natural gas prices nor the adoption of renewable energy significantly reduced the life of coal units. Both have been widely touted by politicians and business leaders as the market-based drivers of coal plant retirement.

However, while adoption of renewable energy alone did not reduce coal units’ life spans, the average use of each source of renewable energy in an area did have a significant impact. Coal units operating in regions with high average renewable energy use retired an average of 15 months earlier.

It is important to note that a large number of coal plants were already nearing the end of their lifecycles during this period. But through statistical modeling, we were able to isolate the impact of each of these interventions on accelerating the retirement of a given unit.

Why It Matters

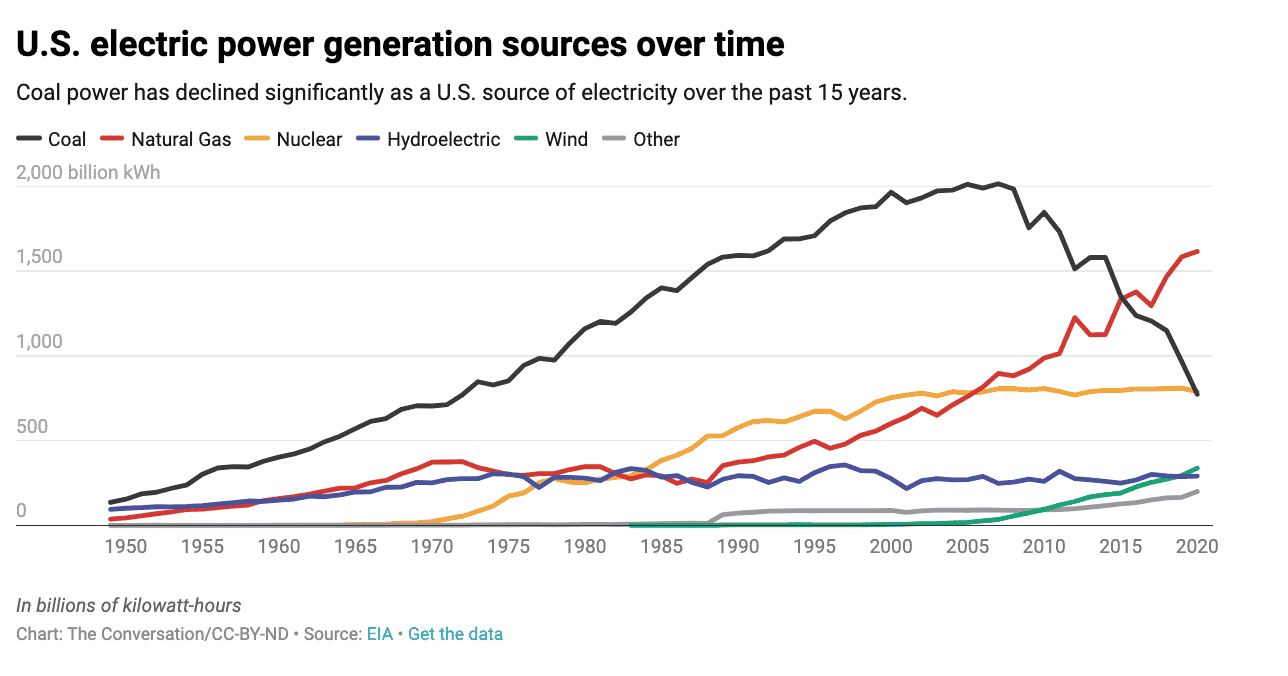

A rapid transition away from carbon-intensive energy sources such as coal is essential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet. Burning coal releases nearly twice as much carbon dioxide per unit of energy produced as natural gas does, and the natural gas contribution to global warming is significant.

From 2011 through 2018, coal-fired generating capacity in the U.S. contracted by 23%. We estimate that the emissions impact of the accelerated retirements we studied was equivalent to taking 38 million typical passenger cars off the road.

The common narrative has been that market forces and economics have driven the demise of coal. However, our research suggests that a continued focus on federal policy is a more effective route for reducing emissions.

The Biden administration has already halted new leases for coal, oil and gas extraction on federal lands. And its climate task force – which includes the Cabinet-level department and agency heads – met in February to start coordinating government-wide climate change solutions. Those likely will include new regulations and could include a price on carbon.

What’s Next

Our current work sheds light on where responsibility lies for the acceleration of coal-fired power unit retirements through late 2016.

Next, we are interested in expanding on our findings about differences between renewable energy use and initial adoption. Understanding how to increase use of renewable sources, while creating new businesses and jobs, is a critical research agenda for addressing climate change.

David Drake is an assistant professor of strategy, entrepreneurship and operations management at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Jeffrey York is an associate professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Disclosure statement: The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Reposted with permission from The Conversation.

- Major Milestone: More than 100,000 MW Worth of Coal-Fired Power ...

- Coal Will Not Bring Appalachia Back to Life, But Tech and ...

- Renewables Beat Coal in the U.S. for the First Time This April ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe