Even the most crowded cities make room for parks. That’s because everyone knows the benefits. Protecting wild spaces allows us to leave a wealth of unspoiled nature for our kids.

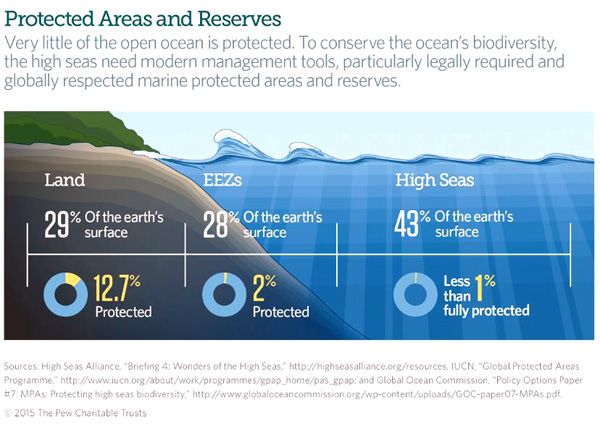

Governments have made some progress establishing wilderness areas on dry land, which makes up just 29 percent of Earth’s surface. Consider that nearly 13 percent is set aside and off limits to the most destructive human activities.

Now consider that there’s no way to do the same for almost half the planet.

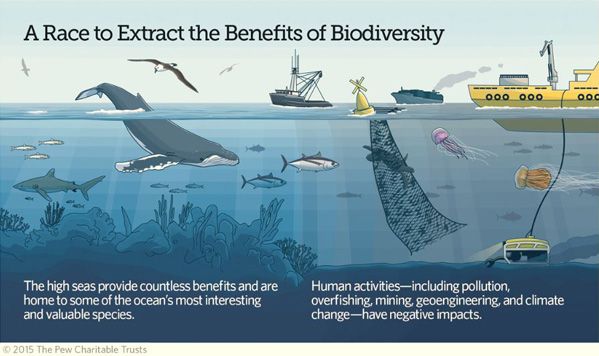

The high seas, or ocean areas beyond national jurisdiction, cover nearly half of Earth’s surface. The open ocean is one of the largest reservoirs of biodiversity on the planet. Species, such as whales, tunas and sharks, spend much of their lives on the high seas, migrating along the highways and byways of great ocean basins from feeding to spawning grounds, and back again. Others spend their entire lives in the high seas, living and breeding along the mighty submerged mountain ranges that make up the sea floor.

Discoveries made in ancient, deep-sea coral fields and on seamounts teeming with life yield potentially life-saving medicines and enhance our understanding of global biodiversity.

The high seas also provide critical ecosystem services for our planet—from fisheries to climate regulation. A report published by the Global Ocean Commission estimates the economic value of carbon storage by the high seas range from US$74 billion to US$222 billion per year considerably more than the US$16 billion generated by high seas fisheries annually.

The ocean beyond national boundaries is wondrous and teeming with life. But this natural beauty is being destroyed one net, one plastic bottle at a time.

All the garbage we dump into the water, all of the stocks we fish to depletion, mining, geo-engineering, the impacts add up to real trouble for the high seas. And right now there is no way to currently establish an area protected from these activities on the high seas (the Southern Ocean is an exception where many countries are working hard to protect special places like the Ross Sea but have come up short because a small minority of countries have objected).

Scientists consider that marine reserves—think large parks at sea—are a critical ocean management tool. They safeguard biodiversity, habitats, and support ecological resilience against impacts of climate change to the ocean. But there’s no way to establish a fully protected reserve in the high seas even though there’s been more than a decade of dialogue on why we must find a way to do it.

Discussion about the need for a legal instrument to comprehensively protect marine life in the high seas has been ongoing at the United Nations since 2003 when it was raised by Brazil and Mexico in the context of deliberations on how to address destructive deep-sea fishing methods like bottom trawling. The Ad hoc open ended informal working group on the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction, known more simply as BBNJ, was first convened in 2006 by the UN General Assembly to discuss those issues.

In 2011, the BBNJ working group—which was still meeting—recommended the General Assembly initiate a process to identify the gaps and ways forward for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction including the possible development of a new international instrument under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

In 2012, at the Rio+20 Summit in Brazil, government leaders committed to take a decision on the development of this new international instrument under UNCLOS before the end of the 69th session of the General Assembly, which began in September 2014 and will end in September 2015.

The time is now. The decision on whether to launch negotiations is being taken up this week at the UN in New York, at the final meeting of the BBNJ working group and what’s at stake is clear. Either governments do not agree to work together to improve the management of areas beyond national jurisdiction, and migratory species will continue to decline, pirate fishers will continue to have a safe haven at sea and marine reserves will be limited to national waters. Or, if governments do agree to join forces under the aegis of a new UN agreement to protect the high seas, it will be possible to set aside international marine parks in the most vulnerable and valuable areas, and to stop the degradation.

David Miliband is co-chair of the Global Ocean Commission. He is scheduled to make an address to the delegates to the UN BBNJ working group on Jan. 21 at 13h15.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Protecting the Galapagos Islands

14 Ocean Conservation Wins of 2014

Will Normalized Relations With Cuba Help Restore Florida’s Coral Reefs?

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe