Car Engine Cover, Fishing Net and Plastic Bucket Found in Stomachs of Dead Sperm Whales

Large quantities of marine debris were found in the stomachs of sperm whales that washed up dead in Germany’s North Sea coast earlier this year.

The whales first surfaced in January and February near the coastal town of Tönning in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. After officials ordered a necropsy of the bodies, post-mortem results were announced in a presentation at the Multimar Wattforum Centre on March 23.

Four of the 13 whales had large amounts of plastic waste in their stomachs, and some of the garbage included a 13-meter-long fishing net, a 70-centimeter-long plastic car engine cover and the remains of a plastic bucket, according to a press release from the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park.

“These findings show us the effects of our plastic society: Animals inadvertently take in plastic and other plastic waste and suffer, and at worst, starve with full stomachs,” environment minister Robert Habeck said in a statement (via Google Translate).

“This reminds us that we step up the fight against waste in the sea,” he said.

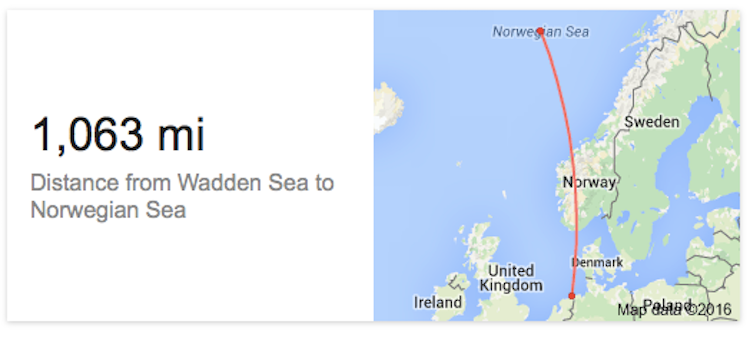

The whales were said to be all young bulls between the ages of 10 to 15 and weighed between 12 to 18 tons. Before surfacing in the shallow waters of the Wadden Sea in the North Sea, scientists suspected that the last time the whales had anything to eat besides plastic trash was in the Norwegian Sea.

According to the press release, male sperm whales in this population spend their winter in the North Atlantic but in their search for food, they mistakenly migrated to the food-poor North Sea.

Ursula Siebert from the Hanover Veterinary College told MailOnline she does not believe the whales died from consuming marine debris. Instead, she said that heavy storms in the north-eastern Atlantic pushed squid—the sperm whales’ main source of food—into the North Sea. She said the whales followed the squid into shallow waters before finally beaching on the shoreline.

As the Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) explained, without support from the water, the sheer weight of the whales crushed their lungs and other organs, leading to death.

Part of a car engine and buckets are found inside whales that washed up on a German beach https://t.co/CRlpTjbn82 pic.twitter.com/I7tkMexmyX

— Daily Mail Online (@MailOnline) March 25, 2016

While the official cause of death was heart failure, it’s clear that human-caused ocean pollution can have a devastating impact on aquatic life.

“Large amounts of plastic waste were also found in the stomachs of the sperm whales, including fishing nets, parts of a plastic bucket and even a plastic car cover. Although not the direct cause of death, vets suspect that the whales would soon experience major health problems as a result of this toxic waste,” the global conservation nonprofit said.

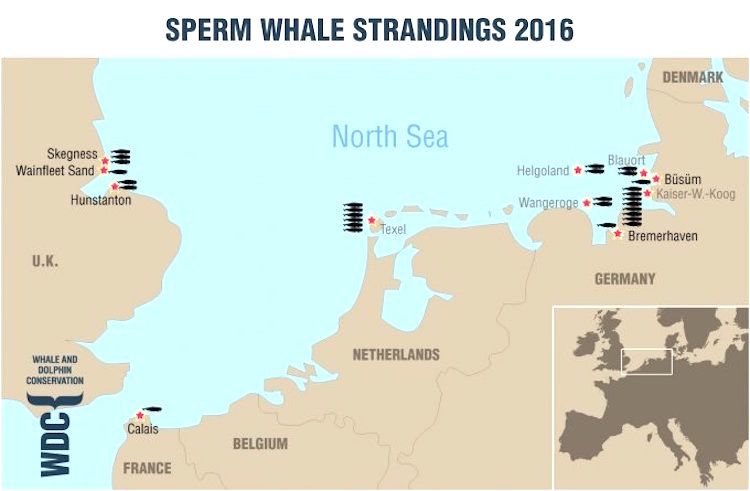

Since January, 29 sperm whales have washed up dead on the shores of Holland, Germany, France and the UK but it’s still unclear how the whales got into difficulty in the first place.

Whale strandings occur naturally, they can also be a result of man-made activity, such as noise from oil and gas exploration, pile driving into the sea bed to build wind farms, military sonar, or from entanglement in fishing gear and collision with boats, the Whale and Dolphin Conservation said in a blog post.

The Whale and Dolphin Conservation pointed out that there are more than 3,000 strandings worldwide every year, but not all of them have to end in tragedy.

The organization is working to prevent more strandings, including marine protected areas, preventing deaths and entanglements in nets, regulating boat traffic and helping to prevent collisions, and addressing pollution, including noise and sonar.

[instagram https://instagram.com/p/BA_qinTqWj1 expand=1]

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Japan Kills 333 Minke Whales Including 200 Pregnant Females

Shocking Footage of Illegal Fishing in the Indian Ocean

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe